Finally, I proposed personally guaranteeing loans to the poor. For several months I met with increasingly senior bank officials, but I couldn’t change their minds. I visited the local bank and tried hard to persuade them to start making loans to the villagers, but they refused, stating that the poor were not creditworthy. But rather than lend money on an ad hoc basis, I wanted to create an institutional answer these people could rely on. I thought, If this small action makes so many people so happy, I should do more of it. The excitement and gratitude they showed in response to this gesture touched me deeply. I reached into my own pocket and lent them the money. We learned that for people living on pennies a day just a few dollars could transform their lives.

Shockingly enough, the total amount of money needed to release all forty-two of them from their servitude was the equivalent of twenty-seven U.S. We found forty-two people trapped in a cycle of poverty by these moneylenders. In many cases, they needed only the tiniest amount of money to support their efforts, but their only option was to borrow from ruthless loan sharks whose usurious terms transformed them into virtual slaves. We got to know the residents and came face-to-face with their struggle to eke out a living. I decided to start going to Jobra, the village next to the university’s campus, every day to see if I could make myself useful to the people living there. What good was I doing for the people suffering on my doorstep? In great agony, I resolved to find a way to help. Nothing I taught accurately reflected the horrors around me. I used to get a thrill from standing in a classroom and teaching elegant economic theories, but I started to dread my own lectures. Thousands of people were roaming the streets hungry, dying of starvation. On top of that, there was a great famine in 1974. The economy was shattered and sliding downhill fast. It had been through a war and had just become an independent country (prior to 1971, Bangladesh was part of Pakistan). In 1971 I returned to Bangladesh where I became a professor and head of the department of economics at the University of Chittagong.Īt the time, Bangladesh was in a terrible state. In 1965 I received a Fulbright Scholarship to study in the United States, where I obtained a PhD in economic development from Vanderbilt University. I did well in school and went on to study economics at a Bangladeshi university. My parents certainly believed in me, but I don’t think either of them could have imagined that I would grow up to start a bank-especially one that revolutionized lending in the developing world. My father could have used some of us to help with his business, but his priority was to make sure we all went to college. They had fourteen children, five of whom died very young.

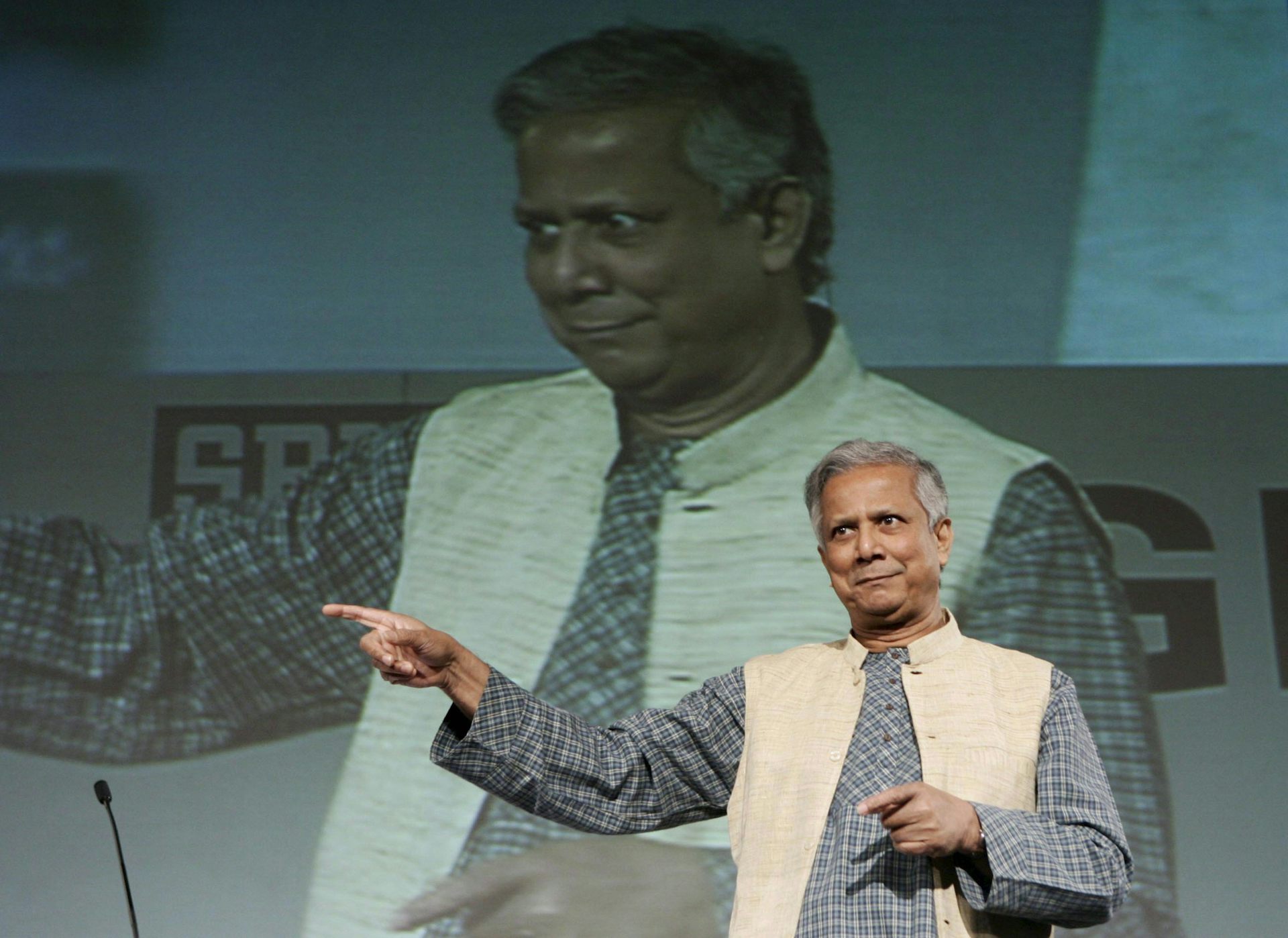

My father went to school through eighth grade and my mother only through fourth. My parents were devout Muslims and hard workers, but they were largely uneducated. We were a very modest, low-income family and lived on a busy street in the heart of town above my father’s jewelry shop. I was born in Chittagong, a port city in Bangladesh, in 1940. Professor Yunus is a member of the board of the United Nations Foundation and has received numerous international awards for his humanitarian endeavors.MUHAMMAD YUNUS NOBEL PEACE PRIZE RECIPIENT Through the last quarter of a century, the bank has stood as the flagship of a 100-country network of similar institutions, enabling millions to escape poverty through individual economic empowerment. In 1983, he established the Grameen (Village) Bank, founded on his conviction that credit is a fundamental human right.

#Muhammad yunus religion free#

Yunus realized that by means of small loans and financial services, he could help the poor free themselves from poverty. From his own pocket, Yunus made a loan to a group of women who repaid the funds and, for the first time, made a small profit. Considered poor credit risks, the artisans were forced to borrow money at high interest rates to purchase bamboo and made no profit after repaying moneylenders. It began in 1976, when he saw village basket weavers living in abject poverty despite their skill. Economist and Nobel Peace Laureate Muhammad Yunus has become internationally renowned for his revolutionary system of micro-credit (small loans to entrepreneurs too poor to qualify for traditional bank loans) that has helped millions to escape poverty.īorn in the seaport city of Chittagong, Bangladesh, Yunus’ life is motivated by his vision of a world without poverty.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)